Neurophysiology of Learning

Have you ever wondered how learning works exactly? After reading this article, you will know exactly what is happening in your brain, whenever you learn something new.

Storing memories

Many experts believe that we store memories via a three-step process: first, we perceive information via our senses, then we store and process it in short-term memory, and finally, some memories, we store in long-term memory. Since we do not need to retain everything in our brain, the process acts as a filter that protects us from the flood of information we are confronted with every day. Important information gradually transfers from short-term memory to long-term memory. The more often information is repeated or used and the more emotionally charged it is, the more likely it is to eventually end up in long-term memory to be retained.

Short-term memory

has a fairly limited capacity. It can store about four to seven items for no more than 20 or 30 seconds each. This capacity can be increased via various memory strategies. For example, a ten-digit number like 8005840392 can overwhelm the short-term memory. However, when broken down into parts, as with a phone number, 800-584-0-392 it can remain in short-term memory long enough for us to dial it. We group the available information, so that it can be remembered more easily. This is called chunking.

Chunks

are a collection of information that have strong associations with each other, but weak associations with items within other chunks. Simply put, a chunk is a collection of related information. Something like a schema, a learning unit, or a functional unit. It has no clear boundary and there are no fixed chunks. Each person forms his or her own units. Thus, the word chunk is more of an abstract concept than clearly defined.

Chunks can be used to learn something new or interconnect topics with each other. Or we get new information on a topic for which we already have chunks in the long-term memory. In this case, we usually find it easier to remember something because we can link it to the information we already have. The more extensive the mental library of learning units, the easier it is to remember. So in general, if you want to learn something new, look at the big picture first to give your brain some orientation. This way it can perceive the context, and you can add details to the framework later on.

When we learn something new, networks are built from the information units. Short-term memory can usually handle 4 -7 chunks at a time. When first learning a concept or technique to solve a problem, the entire working memory (aka short-term memory) is involved. Whenever we fragment a concept, the individual components will connect more easily and smoothly. Thus, only one space in the working memory is occupied. The rest of the working memory remains free. By fragmenting the material, the amount of information available in the working memory has, in a sense, increased. At the same time, it is easier to make new connections. Gradually, the learner recognizes connections between the new information and chunks that are already stored.

Modes of attention

Our brain operates primarily in two predominant modes of attention: focused thinking (the task-positive network) and fuzzy thinking (the task-negative network). These are called networks because they are made up of interconnected neurons (cells in the central nervous system) and act as electrical circuits in the brain. The focused mindset is active when you actively engage in a task and focus on it. The fuzzy mode of thinking is active when thoughts “digress,” colloquially known as daydream mode. Here seemingly disparate thoughts (from different subject areas) can be combined so that subject areas can be logically connected. We thus develop an intuitive assessment of topics. This brain state, characterized by the flow of connections between different ideas and thoughts, is responsible for the moments of highest creativity and insight, when we are able to solve problems that previously seemed unsolvable.

These two attention networks are exclusive: when one is active, the other is not. The switch between daydreaming and attention is controlled in a part of the brain called the insula. This is an important structure that lies about one centimeter below the surface of the skull.

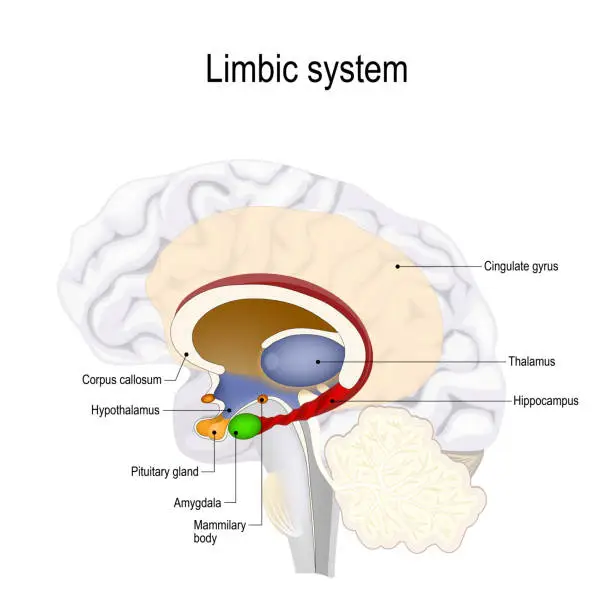

Another important structure in the brain, concerning learning, is the hippocampus. It is located about in the middle of the brain and is part of the limbic system, one of the oldest parts of our brain that regulates automated behaviors and emotions. The hippocampus is responsible for learning and remembering facts and events. Each separate sensation travels to the hippocampus, which combines these perceptions into a single experience. Without the hippocampus, it is not possible to store new memories in the cortex.

Another important structure in the brain, concerning learning, is the hippocampus. It is located about in the middle of the brain and is part of the limbic system, one of the oldest parts of our brain that regulates automated behaviors and emotions. The hippocampus is responsible for learning and remembering facts and events. Each separate sensation travels to the hippocampus, which combines these perceptions into a single experience. Without the hippocampus, it is not possible to store new memories in the cortex.

Experts believe that the hippocampus, along with another part of the brain called the frontal cortex, is responsible for analyzing different sensory inputs and deciding whether they are worth remembering. If they are, they can be incorporated into long-term memory, that is, stored in different parts of the brain. And this happens via neural networks.

Encoding information

Although a memory begins with perception, it is encoded and stored using electricity and chemistry. Learning something new, neurons connect to other cells at a point called a synapse. All brain processes take place at these synapses, where electrical impulses or chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) jump across the gaps between cells like messages. The electrical firing in a neuron triggers the release of chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. These neurotransmitters diffuse through the spaces between cells and connect with neighboring cells. They are enormously important for learning, which is why we will return to them in more detail in a moment. Each brain cell can form thousands of such connections, so a typical brain has about 100 trillion synapses.

Learning and remembering do not happen by changing the overall structure of the brain or by creating neurons, but by establishing connections between cells that change during learning. The connections between brain cells are not fixed, but are constantly changing. Brain cells work together in a network and organize themselves into groups that specialize in different ways of processing information. When one brain cell sends signals to another, the synapse between the two becomes stronger. The more signals sent, the stronger the connection becomes. So with each new experience, the physical structure of the brain is slightly altered.

Neurotransmitter involved in learning

As indicated above, neurotransmitters are crucial in the communication between neurons. Most neurons in the cortex carry information about what is going on around us and what is currently happening in and to the body. The brain also has a number of diffuse projection neuromodulator systems that assess information, not about the content of an experience, but about its meaning and value for one’s future. In this context, acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin are especially important.

Acetylcholine neurons form neuromodulatory connections with the cortex that are particularly important for focused learning when attention is high. Thus, they increase our focus.

Our dopamine release is responsible for our motivation and is produced in the brain stem. It is released when we are interested in something, open-minded and curious, focused on a goal, and/or working to achieve something. Dopaminergic neurons are part of our reward system. It is not only responsible for sensing a reward, but also for predicting future rewards. It motivates you to do something that may not be rewarding at the moment, but will lead to a much better reward in the future. Addictive drugs, for example, artificially increase dopamine activity and trick the brain into thinking that something wonderful is about to happen or they directly increase secretion of dopamine.

To be able to focus on something, the brain needs just the right amount of the so-called catecholamines – particularly dopamine and norepinephrine – placed at a variety of synapses. To increase dopamine levels in a learning situation, the content must be relevant, i.e., the learner must recognize the value (e.g., potential reward) from unlocking the content. One way to achieve this is to make learning situations as “real” and “personal” as possible, e.g., by using advanced simulations or games. Or by rewarding certain activities

Norepinephrine can be released during competitive activities or when we feel pressure to perform, such as when we have a deadline to meet. It makes us feel alert and awake.

Last but not least, Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that strongly influences our social life. Serotonin levels are also closely related to risk-taking behaviors, as these are more likely to occur with elevated serotonin levels. That might not seem directly related to learning, but if we increase our willingness to take risks, we also increase the probability to try something new, make mistakes and ask difficult questions.

To put this all into very easy words: Every time we do something, we have to repeat it or give it emotional meaning, so new pathways are formed and trained. In the realm of personal development, there is a quite famous mnemonic picture for this, which might make it easier for you to remember: Learning something new is like scarfing through the brushwood for the first time. It is very tough, takes a long time and there is only a little path. But the more you walk that path (repeat what you have learned), the more established it gets. It gets bigger and bigger over time. There are more and more connections leading to the path and in the end you have a solid street that you can travel on.

I hope, with this in mind, you will find it easier to tackle new topics in the future and actively create your own learning experience. I will give you some inspiration on how you can do that (hands on) in the upcoming blog posts! So stay tuned!